Taking credit for building credit with Roger Morris, ex-COO Zoro Card

How slack communities, a fearless attitude and a lot of help from the fintech community helped Roger go from college drop-out to COO with millions raised in 5 years.

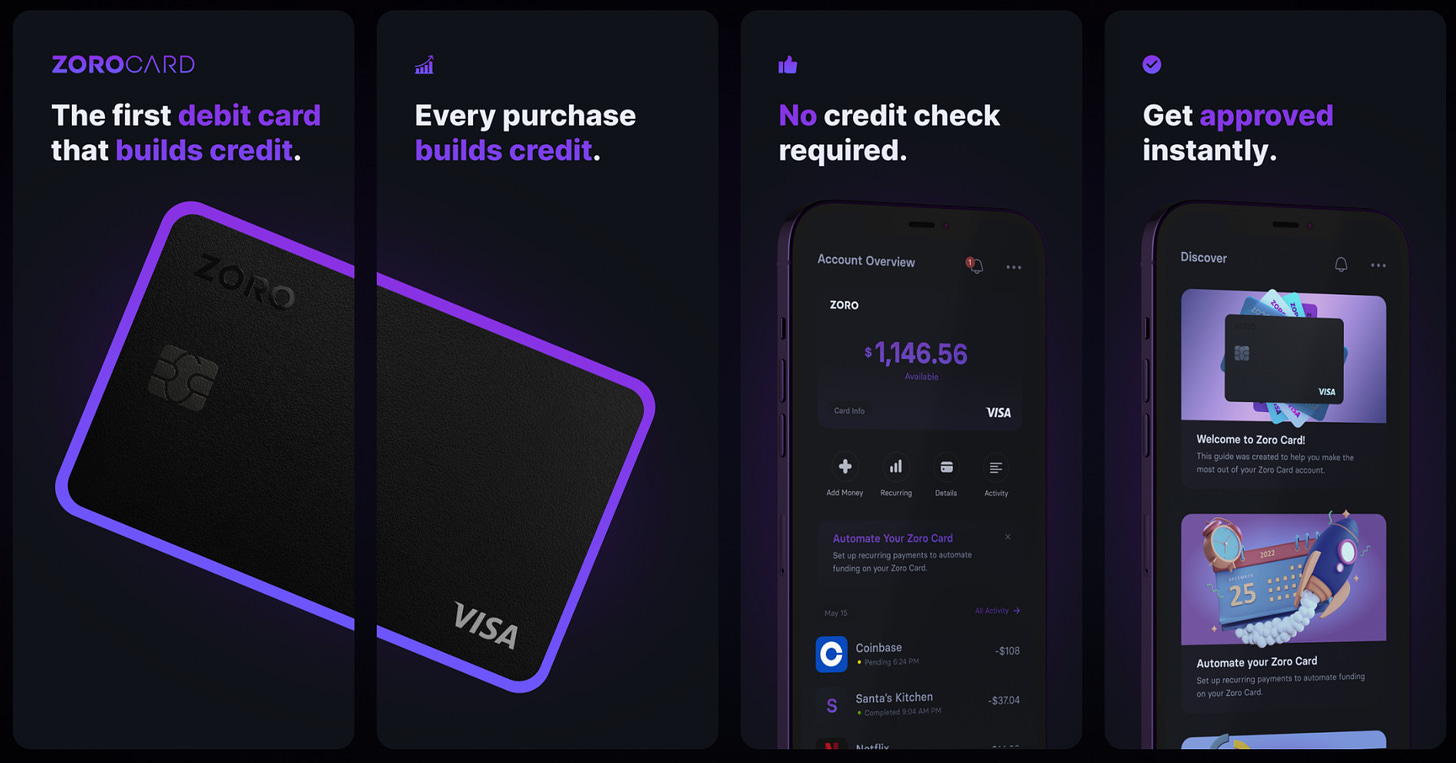

This week we hear from Roger Morris, former Co-founder and COO of Zoro Card.

During college, after being inspired by his college professor, Roger saw his future in entrepreneurship. He prioritized a new fintech start-up which was based on his own (rather painful) experience building credit. Over the course of five years, he learned how to build, who to build for, how to raise money - and he did this with the support of the incredible fintech ecosystem.

He talks about:

Founder story

Two big lessons about building fintech

Four factors for founders to consider if they’re concerned about the future of their business

Specific advice about taking care of yourself in the process

Let’s hear his journey.

Rob: Welcome to Soft Landing. You’re our first interviewee, so thanks for sharing your insights with other entrepreneurs. Let’s start with hearing more about you.

Tell us why you got into entrepreneurship?

Roger: I had a quarter-life crisis in college. I didn't really know I wanted to major in and I ended up taking a class at the business school. And there was a professor at the business school, Dave Harrison. He was a former chief marketing officer in Fortune 500 companies, and also was a serial entrepreneur, and was just very inspiring guy. He turned me on to the idea of doing business for a living.

I spent maybe a year or two just like trying to think of good ideas. I started an online gift shop that didn't make a single sale, but but we had we had products and we had drop-shipping setup and it was more of a learning exercise and a taste of what’s to come.

How did you go from quarter-life crisis to building Zoro?

Roger: In my sophomore year I met Zak, who became my co founder - I thought he was really smart and had been working on a great idea already. We were in a class together, we wrote a business plan together for a class project for a credit builder. And after that, we're just like, let's do this for real, let's actually make happen.

I was already primed for it and then within a short time, we both decided that if we were going to do it for real, we needed to drop out of school. And so we did and we spent the next five years building Zoro Card.

How did you learn how to build a credit-builder card?

Roger: As a freshman I’d used a secure credit card to build credit myself. It was just a really bad experience, and expensive. I was like, ‘this sucks’. There should be a better way to build credit. So I sort of understood the problem.

I didn't know anything about finance or banking or any of that stuff like that and had to learn the hard way.

“We wanted build something knowing nothing about it, and knowing nobody in the space. That's why it took five years. If I went and started it today, I could have probably done it in like one year.”

So how did you figure it out?

Roger: It was a grind. You just have to be willing to talk to a lot of people - we probably spent more time talking to people in year 1 than building anything. The big unlock was when George Kurtyka from Joust added me to the This Week In Fintech (formerly Finnovation) Slack group.

This was a game changer. I suddenly had access to all of the most relevant people, all gathering in one place. I could talk to them and ask questions and engage with the community.

I was learning so much just by reading what other people were asking. And then over time I started knowing enough that I could answer other people's questions. It was just a slow, gradual process that took a long time.

What was your biggest learnings about building fintech?

Roger: If you really think about what the financial system is, from first principles, it's really just one big ledger, or a bunch of ledgers that are sort of loosely integrated with each other. There's reconciliation process between each ledger. But it's like, that's all it is.

When you think of it in those terms, it gives you this almost like freedom to explore things that you might otherwise dismiss as being “Oh, you can't do that”. We learned that it’s a question of how do you justify what you're doing legally, so that you're allowed to do it.

We built Zoro by asking questions like “what exactly is the debit card? What is building credit?”

The deeper you go, the more you realize that many of the assumptions we make about the financial system are arbitrary.

Sounds easy…

Roger: LOL, not always! For example, the other big learning was about how slow the feedback cycles in fintech can be. Once you sign a bank partner, you're locked in that bank partner for three to five years. You sign a BaaS provider, you're stuck with that BaaS provider. There's nothing you can do about it, especially if you’re cash constrained - so you're locked into that contract. This leaves very little room to make mistakes.

And as a first time entrepreneur, you're gonna make a ton of mistakes, but with infrastructure decisions you can't learn from them and adjust. One of the hallmarks of good software engineering is the ability to make changes quickly and with low friction. That ability doesn't exist very much in banking. I think that's a key thing that's holding back innovation - the feedback cycles are too long. Especially when you’re cash constrained.

Five years is a long time to work on a project. Help us understand what stood out by sharing some of the highs and lows of this experience.

Roger: That’s a tough one.

High 1: First investor check

The first time we closed an investor check. We were weeks away from completely running out of cash from a small friends and family round ($40k). We needed to be paid, our CTO needed to get paid and our BaaS provider needed to get paid as well. That check was a lifesaver and a real high point.

Low: The journey to find a banking partner

We needed to pivot away from our BaaS provider just after raising our first check so we set out to find a banking partner. The initial conversations with banks were a disaster, because they would ask us a basic question about KYC. And I had no idea what KYC was!

High 2: Finding our new banking partner

Even though it sucks to be told ‘no’ over and over, something just just kept driving us forward. We had to learn more and more and eventually, we did find a bank partner - that was definitely a peak.

What do you think went wrong ultimately?

Roger: After integrating with our new banking partner we had a long period of integration hell which was the beginning of the end for the business. We never got to a point where we felt like, “Okay, we're ready to scale.”

We had 70,000 people on our waitlist and ran a limited launch - we were reporting into one of the credit bureaus out of the three, we had provisional approval from the other two but it felt like the majority of our attention was managing integrations with vendors. We felt stuck.

On reflection, I think we could have been smarter about the way we architected it (we built our own ledger), and maybe even simplified the product in a number of ways. For example, we could have limited it to subscription only card for some period of time. But we tried to launch a full neobank out of the gate, which I think was a naive decision that I definitely wouldn’t repeat.

We just couldn’t get our product into the hands of the 70k customers on our waitlist.

How did you approach the end of your company? When did you know the writing was on the wall?

Roger: During our journey there were a lot of people who said, ‘you're never going to succeed building this product’. And then we did it - we actually launched the product!

We did a lot of stuff that gave us this underlying belief that we were able to overcome really long odds. I think that gave us that made it harder to admit defeat, because we had survived the odds so many times in the past.

So there wasn't exactly a specific moment. I would give up for a few days and then a few days later get really energized. And then some adverse event would happen or something else would go wrong. And I’d feel down in the dumps again. That cycle was mentally difficult and taxing and I think by the end of it, I was really burned out.

The big catalyst was failing to raise money and knowing deep down ‘okay, we're out of time’. The market changed so much in late 2021 just as we were raising and I started to come to terms with the fact that we were not going to be able to raise money.

How did you prepare for your exit?

Roger: There was an early interest in an acquihire-type scenario. We received an offer that involved relocating, but we never got to an offer that we were super excited about. We were burned out and so didn't move forward with any of the acquisition opportunities. Our optimism for seeking acquisition gradually petered out.

Then one day our inability to secure funding meant that we couldn’t pay our invoices. This led to the banking partner shutting down the program.

How did you prepare your team?

Roger: We had some difficult conversations with our team, but we decided to be as transparent as possible, and as optimistic as possible.

We asked our team if they'd be willing to take a lower salary. Almost everyone on the team said ‘yes’, and we ended up cutting salaries by an average of 45%. To this day, it still blows my mind. I have a lot of love and appreciation for the team and what they were willing to do in order to try to see this through. Especially given that we still didn't succeed. So that was a tough pill to swallow. The thing I had the most trouble with, in terms of failure, was just feeling like I had let the team down.

I think Soft Landing has had such a great reception is because many other founders are facing a similar situation and don’t know where to go to for help - what advice would you give them?

Roger: I also have a lot of friends going through this right now. From my experience I’d break it down into a few things:

Who are you in relation to what you've built? Are you being objective? A lot of founders have invested so much of themselves into the company they've built, and so it's hard for them to take a step back and look at the situation they're in objectively.

Have you considered what success means in your specific industry? The more competitive and less differentiated something is that you're working on and the higher bar there is for execution.

Have you selected the right problem? What problem are you solving and why? The less clear your problem statement is, the higher the bar is to succeed. So if you're gonna build a neobank, it had better be a damn good neobank. Are you really building a world class product, if it’s just on okay product, it’s going to be really hard to succeed.

Have you picked the right market to match your product? If you figure out something that's a novel solution to a problem that's currently unaddressed, the bar for success is lower, which is clearly better.

I think about these things a lot when I look for opportunities that excite me as a founder today. I'm definitely going to be a lot more cautious about building a startup in a space that's as competitive as cards and neobanks.

And where did you, Roger, personally fit into all of this?

Roger: If you're afraid about yourself and your own future, I think sometimes you're driven to make suboptimal decisions. Especially when it comes to letting go of your start-up.

I felt that I had gained a lot of useful experience, I built a really good network. I knew that I was somebody that could be employed. I didn't know when, where or how, but I always had confidence in myself that I'll be okay.

On reflection, though, I probably neglected myself a little more than I should have. I didn't have like any savings and I had to borrow money from my family to make ends meet until I had the next job. I’m lucky I had that support network. There's definitely some ways that I would recommend others do it differently

For example?

Roger: Here’s a few.

Make decisions earlier when you have runway. I think if you're going to shut down your company, I would recommend to do it when you still have enough runway to give everyone a reasonable severance payment. If you wait too late, you’ll be making decisions through a lens of fear and they won’t be good decisions.

Make sure you have a personal safety net so you can get on your feet again. I'm lucky that I had family that could help me make ends meet. But if I didn't have that, I would have had to take on debt, or just drive for Uber. Being in a precarious financial situation would have limited my ability to find the best opportunity for myself.

Make sure you’re paying yourself fairly. I took pride in being one of the the lowest paid people on the team. Our employees made way more than me and my co founders. We did like an inverse correlation with the equity offered and how much we got paid. But ultimately by underpaying myself, it made it harder to bounce back later.

Pick good investors who are real partners. Our investors were great - Greg Beaufait from from Dundee Ventures was incredibly supportive and did everything to make sure things were good for the founders and our team. He even put a little extra cash into the business to make sure we were looked after. He was amazing, I really have nothing but good things to say about him. That's why I call him out by name because I want him to get some recognition for that. The venture world needs more people like him.

So we don’t talk too often about failure - based on your experience, what would you say to future or current founders?

Roger: It’s a good question that’s not asked enough. The experience taught me a personal philosophy I’m happy to share.

“I think the healthiest mindset to go into starting a new venture is to approach the start-up with the goal outcome being who you become in the process versus you know, the outcome of the company.”

It makes the whole journey more rewarding and regardless of the outcome, so then you can feel good about a failure because you know, I did my best. I grew a lot as a person. That experience is something you carry with you for the rest of your life. So from that perspective, I think it's a very worthwhile thing to do, regardless of the outcome.

Obviously you want to start a successful company, that's a given. But if you can zoom out a little bit and reframe what your goals are to be about who you are, who you become, the growth that you experience, you cannot fail.

Weekly musings

Soft Landing has resonated and received more interest that I could have imagined. I’ve heard from press, VCs, fellow entrepreneurs, and folks wanting to jump into start-up land but worried about what they’ll find.

I’m reading Ray Dalio’s book, The Changing World Order, about the factors that predict the decline of an empire (sorry, USA, this one must sting). My favorite quote of Ray’s is “If you’re not failing, you’re not pushing your limits, you’re not maximizing your potential”.

I’m meeting a lot of fintech founders in Mexico City right now. This scene is on fire - super smart people, interesting problems, high ambition and risk appetites. If you’re in Mexico City, let’s share a coffee or beer.

Community help needed

This section is where I can hopefully make some connections within our community.

One member asked: “could you help me find bankers be willing to talk about loan underwriting pain-points?”

Another member asked: “do you have any advice about failing within a corporate environment where it can be seen as career suicide?”

A third member asked: “do you know of any good marketplaces for start-ups looking to sell up?”

If you need help or can offer it to the Soft Landing community, please reach out. See you next week.

Rob.